1960s: Teacher Power

In May 1960 the United Federation of Teachers of New York City threatened to strike if the school board did not agree to hold a collective bargaining election for New York teachers. After months of stalling by the board, the teachers went out on a very successful one-day strike in November on Election Day’ This resulted in a June 1961 vote, overwhelmingly in favor of collective bargaining. The following December the teachers of New York voted decisively for the UFT against two rival organizations.

After failing to negotiate a contract with the recalcitrant board, the UFT called the teachers out again in April, despite anti-union media hysteria and New York laws barring public employee strikes’ The teachers achieved a $700 across-the-board raise, grievance and arbitration procedures, and improved working conditions. A new era had arrived.

The events in New York were like a spark touching off a fire in a very dry forest. The national AFT grew from less than 60,000 members in 1960 to over 200,000 by the end of the decade. More than 300 teacher strikes occurred throughout the country during the ten years following UFT’s one-day walkout. The NEA was forced to move in the direction of becoming a real union or be put out of business by its rapidly expanding rival, reluctantly supporting strikes for teacher demands “as a last resort” and beginning to eliminate administrators from some affiliates’ units.

In California, changes no less dramatic were taking place. Inspired by the example of their brothers and sisters across the country, new members flocked into the California Federation of Teachers (the “State” was officially dropped from the name at the 1963 convention). The organization multiplied five-fold, from a few thousand to nearly 15,000 by 1970.

Politically the new decade began auspiciously for the CSFT. A spirited defense of students who had been violently attacked by police while peacefully protesting a HUAC hearing in San Francisco in May, 1960 led to the chartering of a string of new locals in the colleges, starting with San Francisco State Local 1352.

Teacher unionism did not emerge suddenly in the 60s from a vacuum. The “profession”, nearly all female in the founding days of the AFT, had become somewhat gender-integrated by the end of the 50s, although women remained a large majority, especially in elementary grades. While in other periods women often led teacher struggles, in the late 50s increasing numbers of men appeared to have brought with them a heightened militancy, along with their expectations for a “family wage.” The influx of veterans in the mid-50s from the Korean War seemed to stiffen the backbone of teachers in many districts, following the pattern of postwar gains in membership and militance. At the same time, what had traditionally been a largely middle class occupation began to attract more job-seekers from blue collar families with a greater awareness of an affinity to unions. (The effects of this sociological shift, however, were mixed’ Some teachers from working class backgrounds, eager to clamber up into middle class respectability, would have nothing to do with unions.)

By the mid 60s political activism in the country was rising to a post-war high. The great civil rights, student and anti-war movements swept away the fearful, conformist atmosphere of the Cold War. In the labor movement, the AFL-CIO put money and organizers into the public sector, with excellent results: millions of members in services a government work were added to unions in those years, including teachers.

But it took some doing for all this to happen. Looking back at his local in 1960 from the vantage of the 80s, Raoul Teilhet noted that “It was more like joining the French Underground than a union: we had more secret members than public members.” After conservative state senator Hugh Burns redbaited the CSFT’s legislative advocate Andrew Barrigan in early 1962, Barrigan’s credibility was sufficiently damaged that he felt it best to resign. The CSFT had to win a number of legislative and legal victories before the lingering effects of the Cold War in education could be shaken off.

The CFT’s growth spurt was aided by passage in 1961 of the Brown Act, which granted public employees in California the right to join or not join the employee organization of their choice. Although explicitly excluding collective bargaining, it granted a broad scope to ‘meet and confer’ rights for teacher organizations. The Brown Act gave the union the legal ability to organize and recruit members, and the right to be recognized as a legitimate employee organization.

Maurice Englander was elected CSFT president in 1962, the same year that conservative Max Rafferty became state Superintendent of Instruction. During his presidency the organization grew and won a number of important legal and legislative victories.

A San Francisco Federation of Teachers activist and chair of the English Department at Lowell High School, Englander had served as CSFT vice president under Lou Eilerman, and supported the expansion of the union into the state university and community college systems. He reasoned that the imprimatur of professors - as with Albert Einstein and John Dewey in the past – would lend prestige to the CSFT and boost its image as a professional organization for K-12 teachers, undercutting CTA’s argument that unions weren’t “professional”. For similar reasons he helped to establish the Union Review, an academic quarterly devoted to labor issues; it was to provide a publishing outlet for professors, thereby recruiting members among the professoriate as well. Don Knapp of the newly-chartered San Francisco State College Local 1352 was named editor. Unfortunately, the Review received little support within or outside the CSFT; it folded after one superb issue. Authors in the short lived Review included labor writer/activist Sidney Lens, U.S. Secretary of Labor Arthur J. Goldberg, education author Myron Lieberman and sociologist Seymour Lipset.

Another CTA argument against the CSFT was the CTA’s insurance programs for teachers. Englander established an insurance trust for the union to offer teachers, too.

Englander chaired the CFT Legislative Committee, which had been formed to assist attorney Joe Genser draft legislation and give testimony in Sacramento; under his direction the CSFT legislative program achieved some notable successes. In 1961 the Fisher Act, supported by the CSFT only after significant amendments abolished the education major. It stated that all teachers must have a bachelor’s degree and credential in an academic subject matter area. As amended it embodied a significant aspect of the CSFT’s position on teaching as a profession: teachers would now command expertise over specific subject areas. Local 771 activist David Creque and CSFT Secretary Farrel Broslawsky helped draft the language eventually passed into law.

Ironically, CTA’s opposition to the Fisher Act ended up working in favor of the bill’s passage. The Association encouraged its members to write letters condemning the proposed law to their legislative representatives. Some of these were read out loud by angry legislators to their colleagues; advocates cited the near-illiteracy of the teachers’ letters as proof of the need for passage of Fisher’s bill.

The same year another important victory was won for teacher rights with passage of the Probationary Teacher Protection Act, AB 337, which provided for mandatory hearing before dismissal. CTA and virtually every other educational organization opposed AB 337, but legislators were convinced by CSFT arguments that included transcripts of courtroom testimony from the case of the three Long Beach teachers Raymond de Groat, Lucille Couvillon-Grieve and Maureen Cameron-Clarke. De Groat had been fired for alleged leftwing political activities ten years before; Couvillon-Grieve and Cameron for defending de Groat. All were probationary teachers, although the case had been lost, the judge while rendering his verdict stated that if he had been a member of the school board, he “would have granted tenure to these three fine teachers;” but current law prevented him from changing the school board’s decision. The judge’s words helped sway the necessary votes to pass AB 337 into law, mandating the right for every teacher to receive a letter stating the reasons for dismissal; a public hearing based on those reasons; and appeal the decision of the hearing to a court on the basis of the procedures of the hearing. The CSFT was assisted by strong lobbying from the California Labor Federation. Passage of the bill capped an 11-year struggle for the CSFT.

In 1962 the Jack Owens case, called by Englander “the Magna Carta for teachers”, came to a successful conclusion. As with Victor Jewett and Ed McGrath before him, Owens – a former northern director for the CTA and president of his local Association – had been fired in 1959 for the heinous crime of “unprofessional conduct,” as determined by the CTA’s ethics commission. The activities that prompted his firing were hosting a series of educational forums and writing letters to the editor of the local newspaper critical of the school district. The CTA found him guilty of violating their code of ethics, the board fired him, and when Owens went to court their decision was upheld. But the state credentials commission refused to revoke his credential, and in1962 an appeals court decision reversed the lower court ruling, finding essentially that the CTA’s committee had no standing to determine a teacher’s “professionalism.” Throughout Owens’ ordeal the Federation raised funds, held rallies and publicized his cause.

In another key case, in 1963 Pasadena teacher Paul Finot was reassigned to home teaching because he refused to shave off the beard he’d grown over summer. A school board member let drop unwise remarks indicating Finot’s union activism was probably the real cause of the disciplinary action. His principal worried publicly about the unsettling effects that the beard might have “on Negro students.” The irony that Finot taught at John Muir High School, whose namesake sported a rather prominent set of whiskers, apparently was lost upon the school board.

In Superior Court he was asked, “Isn’t your beard an outgrowth of your radicalism?” Finot responded, “It is an outgrowth of my six week fishing trip.” The case went to an appeals court in 1967, when Finot was vindicated as the judge declared that “A beard for a man is an expression of his personality”, and “…symbols under appropriate circumstances, merit constitutional protection.”

It was for supporting teachers like de Groat, Couvillon-Grieve, Cameron, Owens and Finot that the CSFT and CFT became known as the “ACLU for teachers.” Although the CFT lost a majority of the cases, enough were won that a body of law was slowly built up around teacher rights; most of the key teacher rights rulings applicable today in California were won by the union in the 60s and early 70s. The string of court losses regarding probationary teachers served another purpose: it gave the CFT ammunition in Sacramento to be able to demonstrate that the probationary protection laws were worthless and needed to be rewritten.

Teacher defense also proved an excellent organizing tool. The CFT attracted many new members for its willingness to fight for teacher rights, no matter what the cost. On the opposite side of the coin, scores of courageous rank and file teachers went through the ordeal of public hearings so that the union’s attorneys could create the case law necessary to protect the employment of future teachers. The union’s attorneys, particularly Howard Berman, later a U.S. Congressman from Los Angeles, and Stewart Weinberg, from the labor law firm of Levy, Van Bourg, Geffner and De Roy, donated countless pro bono hours to their favorite union causes: teachers and farm workers.

One more case deserves special mention, that of Marie Whipp, a P.E. department chair in Antelope Valley. Fired during the 1962-63 school year for defending young women teachers from the sexual advances of older male instructors and for calling her principal a “jackass” for protecting the men, her public hearings, held at night, brought out standing-room crowds of parents and teachers. Whipp, holder of a P.E. for handicapped children credential, was very popular with the children’s parents. The Superintendent lied on the witness stand, and his promising political career came to an end. The Principal broke down under questioning and was fired. However, so was Whipp, since the school board upheld the original firing. She found another job chairing a P.E. department and went on to become a CFT vice-president and later secretary-treasurer.

In December 1963 CFT Convention delegates elected Fred Horn of San Diego president. He led the CFT through a period in which profound transformations were starting to overtake the organization. With full-time staffers in north and south; with a membership of several thousand and expanding; and with an increasing ability to influence legislation in Sacramento, the union was experiencing growing pains. Membership expansion called for a stronger central organization and statewide presence. Centralization, however, ran against the grain of the union’s history, which was characterized by strong locals and a relatively weak, underfunded state office.

Some local leaders stood on principle against strengthening the CFT Resistance to a staff-run union was in part on fears of becoming too much like the CTA, which exercised heavy control over its chapters from large, a centralized bureaucracy. The CFT, by contrast, was a rank and file oriented union, a federation of autonomous locals. Many activists felt it should stay that way. Horn essentially agreed with the issue of autonomy; yet given the surge in membership, his central goal as CFT president, he felt, had to be organizational development.

Horn, like his predecessors, travelled around the state, mostly in the south, to help locals organize. He had a small budget; again, in the CFT presidential tradition, part of his expenses came out of his own pocket. Horn believed in the basic tenets of the broader labor movement. His ideological fervor stood firmly in the tradition of the state teachers’ union, and kept tempo with the other movements for social justice: he was “honored”, for instance, to invite UC Berkeley student Free Speech Movement leader Mario Savio to address the CFT convention in 1964 when Maurice Englander showed up with Savio in tow. (Berkeley graduate students had organized into AFT Local 1570 during the 1964-65 school year.) But a sense of solidarity was no longer enough; a more solid organizational footing was also necessary for effective statewide coordination of the growing California Federation of Teachers.

Horn became ill in spring 1965, and Harley Hiscox, senior vice president, finished Horn’s second term of office. The Executive Council appointed Secretary Farrel Broslawsky vice president. As a result Local 1424 president Raoul Teilhet was appointed to his first statewide office, CFT Secretary. Hiscox, although less of a political leader than his predecessors, demonstrated fine organizational skills. Like Horn he concentrated on creating an appropriate infrastructure for the CFT. Shortly after his brief term of office expired the union hired him as its southern Executive Secretary. Later Hiscox was promoted to Director of Organizing.

In 1965,inspired by the examples of New York and other large urban school districts around the country, Local 1021 President Eddie Irwin persuaded the national AFT to help set up a membership campaign in Los Angeles in preparation for moving toward collective bargaining. The AFT and AFLCIO Industrial Union Department put up the money to hire former CFT Executive Secretary Ralph Schloming to lead the campaign. The lack of a collective bargaining law in the state and divisions among Los Angeles teachers prevented this early effort from achieving success.

Later that same year San Francisco high school teacher Marshall Axelrod became state president at the CFT convention. The rising tide of social and political militance across the country found a resonance in the CFT, with an increasing willingness of teachers to act decisively on their own behalf and in solidarity with the struggle of others. This attitude was reflected in 1965 convention activities. The convention voted to support the struggle of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee, soon to become the United Farmworkers Union. The spectre of Viet Nam raised its head for the first time in discussion and resolutions.

The following year teachers in California began to hit the streets. In Berkeley a picket line of 50 teachers accosted members of the School Board over their failure to act on a detested transfer policy. The first teacher strike in California erupted in Richmond, led by President Bill Wagner of Local 856, Contra Costa County Federation of Teachers. At San Francisco state Local 1352 charter members Leonard Wolf, Mark Linenthal and James Schevill held a public reading of poetry seized by San Francisco police, in a demonstration of opposition to “a passive psychology that will allow gradual erosion of the rights of free expression essential to education.” At UC Berkeley the graduate student local went on strike for recognition, and with the assistance of the Alameda County Central Labor Council, wrung a grievance procedure from the University administration. The theme at the 1966 CFT convention, at which Axelrod was reelected, was “Teacher Power.”

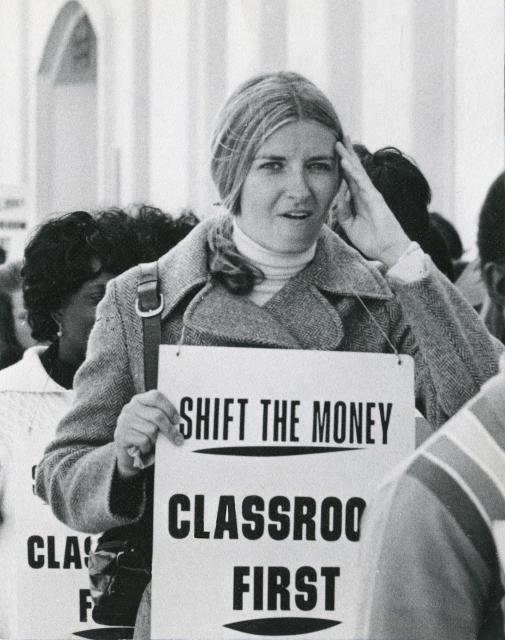

In spring of 1967 the recently-elected Governor of California, Ronald Reagan, slashed the budget of the public schools. Teachers were not inclined to take this quietly. The CFT pulled together a coalition of other unions, students and community organizations, and led a march of 10,000 education supporters in Sacramento. Governor Reagan had refused an invitation to address the demonstration held on the Capitol steps; but he made a dramatic surprise appearance, surrounded by bodyguards. As the Governor appeared, CFT vice-president Miles Myers and a few other desperate CFT leaders held off an angry crowd from storming the platform. While the march failed to generate an influx of school funding, it built teacher morale. The positive publicity for the CFT was enormous among teachers all across the state; and the Governor was put on notice that he faced vocal opposition.

Amid all the turmoil, Axelrod faced the same problem dogging other CFT presidents since the late 50s: how to create and maintain a statewide structure to keep pace with the growth of the membership. He oversaw the implementation in California of the “Coordinated Organizing Program”, created by AFL president Dave Selden and United Auto Workers president Walter Reuther. It represented the best-funded organizing effort of the CFT thus far. With matching money from the national AFT, the CFT and locals, Axelrod hired Abe Newman and Keith Nason to work with East Bay locals and the college groups. Each local received organizing assistance, and the staffers helped to engage the locals in common activities. Axelrod also began a practice that worked so well it was continued into the next decade: he had the CFT issue expansion notes to members, on which it would pay interest and purchase for redemption later on. The notes raised several hundred thousand dollars for organizing. The members bought them enthusiastically, both for ideological principle and their excellent interest rates.

Under the CFT president’s determined prodding, the convention in1967 voted for a considerable raise in state per capita dues, no mean achievement in the face of local resistance. Axelrod’s accomplishment would allow the organization to hire some desperately needed staff and expand its work in the field and in Sacramento. From a relatively modest budget of $90,000 in 1967 the CFT found itself with more than $160,000 to spend the following year, thanks to growth and to the per capita increase. Axelrod, however, was not fated to lead the wealthier CFT. For it was at the December 1967 convention that Pasadena High School teacher Raoul Teilhet was elected president, a position he would hold for 17 years.

In Raoul Teilhet the California Federation of Teachers found the leader needed to shepherd its rise to its greatest accomplishment, collective bargaining for California teachers. Teilhet combined the dynamic force of a charismatic personality, the conviction of deeply held political beliefs, and the boundless energy of a spirited organizer. His vision for the continued growth of teacher unionism was based in the idea that the CFT should stake out more progressive positions than the CTA on every issue possible.

Teilhet became the first full-time president of the CFT. This change in tradition did not go down easily for some longtime CFT activists, who believed that for elected union officials to go on staff was the beginning of the long slide toward a CTA-like bureaucracy, out of touch with the membership and their day-to-day classroom struggles. Teilhet, too, remained committed to an activist organization led by an activist president. But he saw that the days were over when the demands on the office could be handled by a full-time classroom teacher. Working with a seasoned and talented field staff, he set out to advance beyond the gains of nearly a decade of uninterrupted growth. The results probably surprised even him.

Within two years the CFT-a mere few thousand in 1960 – doubled in size again, to nearly 15,000. Feeling the heat of its fast-moving challenger, the CTA began to countenance the unthinkable: throwing out its administrator members, supporting collective bargaining, and endorsing teacher strikes.

The close of the 60s found the AFT on the ascendant in California, as in the rest of the country, riding atop a wave of teacher activism. In 1969 northern California was rocked by the San Francisco and San Jose State strikes, demanding transformations in curriculum to reflect changing student populations. The strikes were led by militant AFT locals and Third World student organizations. Achieving national media coverage, the long strike at San Francisco State exacerbated divisions in the faculty that eventually came back to haunt AFT.

In Los Angeles a 1-day strike called by the Association was followed by the AFT local keeping their members out for another day. The Association realized that a successful job action in the future necessitated a united organization. The result the next year was merger: UTLA (United Teachers of Los Angeles), affiliated with both CTA and CFT. Many in the CFT hoped that this foreshadowed a united teachers union for all of California.