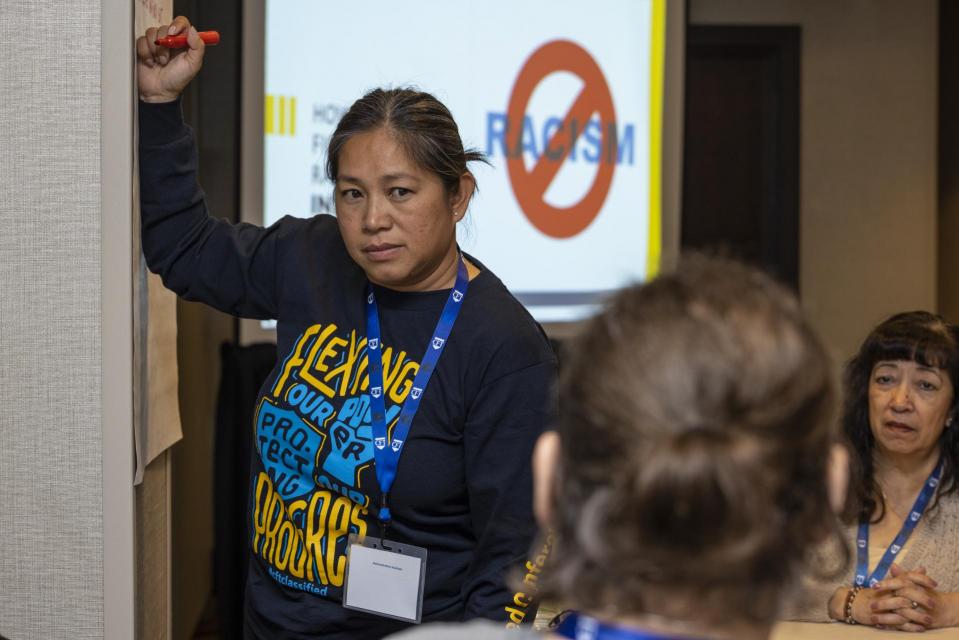

At the workshop, “Anti-Racist Actions We Can Take in Our Personal and Work Lives,” at the annual CCE Conference in San Francisco, Tamika Childs, associate director of AFT’s Union Leadership Institute, told the participants they would have some difficult conversations.

With the help of moderator Lisa Agcaoilli (member of Lawndale Federation of Teachers), Childs asked the attendees what community agreements they’d like to make for everyone to do their best. People made suggestions like, “Respect one another, step up or step back, and speak your own truth.”

The two objectives for the workshop, Childs said, were raising awareness of one’s biases and anti-racism actions to take.

She then asked everyone to stand in a line and to step forward or back in response to questions like: Did your parents graduate from college? Have you been accused of cheating or stealing? Did you start school speaking a language other than English? Afterwards the participants got into small groups and discussed what they learned in the activity and how it made them feel. Comments included that silence could be as loud as racism. The point of the silent exercise, Childs said, was to see that power and privilege exist.

Noting that it was necessary to define racism to be anti- racist, Childs asked for some definitions of the word. People offered ideas including — inequitable systems and polices, using power as a structure to discriminate, and presuming a deficit model of people.

Childs talked about the importance of anti-racism with systems in place that affect us all and then asked people to come up with some practical ways of fighting racism.

“This is not just me talking to you,” she said. “This is us as a group, as peers, colleagues, learning ways that we can combat racism.” When the smaller groups came back together, one participant pointed out the importance of getting beyond bias.

“If you cannot address a person’s basic needs, you cannot engage them in deeper conversation,” she said. “You’re looking at this person, and you create what you see, right? But until you actually have a conversation with the person, then you cannot address the basic needs of the individual.”

Another attendee said they are learning how to respond when people point out prejudices they may not be aware of.

“Coming from a position of privilege, when I’m called out on my implicit biases, something I’ve learned recently is don’t get defensive and don’t shut down,” he said.

“Thank the person for the correction and move on and learn from it.”

Another participant responded to that, saying she created stories in her head about people she worked with but was learning to listen to what they actually said. Childs asked people how they would suggest having more understanding, so they don’t create profiles based on their biases.

One woman, who works with families at a school, says because of her name, people often assume she’s white or Filipina. She says she asks people what their barriers are and tells them she asks these questions so she can help them.

“You have to be vulnerable, and when you’re vulnerable, you allow them to be vulnerable,” she said. “Because I was them, and I think it’s just being honest, being transparent, and being open.”

Having those conversations is important, Childs said. “I can’t tell you how many times I’ve come to do a training, and I’m considered to be the support staff,” she said. “We create these narratives about people without having gotten to know them. All of our stories aren’t the same.”

Other groups shared suggestions they’d come up with about knowing their own and others history and being aware of racism.

Childs agreed that was a good first step to be mindful of what racism looks like. It’s difficult, but necessary to say something, she added, if you hear or see something racist.

“Do you hold on to it because it’s family or friends or a colleague, and it’s uncomfortable?” she asked. “You’ve got to call it out. Make them uncomfortable. It should not be comfortable to be blatantly racist.”