When Josh Brahinsky isn’t teaching “Academic Literacy and Ethos” and “Brain, Mind, and Consciousness” classes to new students at UC Santa Cruz, the lecturer is researching bio-cultural anthropology at Stanford University, teaching at San Jose State, or leading online classes at Bucks County Community College in Pennsylvania.

“UC only pays me $19,900 yearly,” Brahinsky said. “That’s not enough to live on, so I have to make up the difference somewhere else.”

Dolly Wilson has been a registered nurse for 10 years, and has taught at the UCLA School of Nursing for three years. When Wilson isn’t on the Westwood campus, she works as a nurse practitioner at a private urgent care clinic.

“A lecturer’s salary is not commensurate with what we are paid in a medical position,” Wilson said. “It is almost charity work.”

Brahinsky, Wilson and about 6,500 other lecturers on the 10 University of California campuses have been locked in contract negotiations with the administration since last April. Progress has been painfully slow, as described by the UC-AFT bargaining team two days before the lecturers’ statewide contract expired in early February.

“UC has yet to make a serious proposal on any of our key demands,” the team wrote in a bargaining bulletin. UC-AFT is asking for available classes to be assigned to current faculty before hiring new faculty, longer appointment terms, more full-time teaching jobs, compensation for service and professional development work, fair workload standards, and middle class salaries.

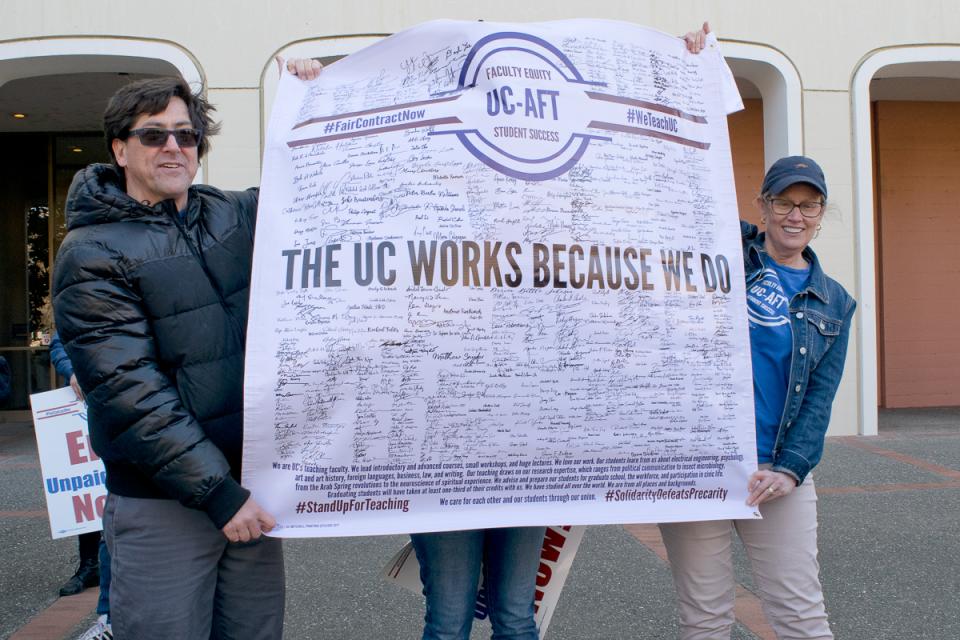

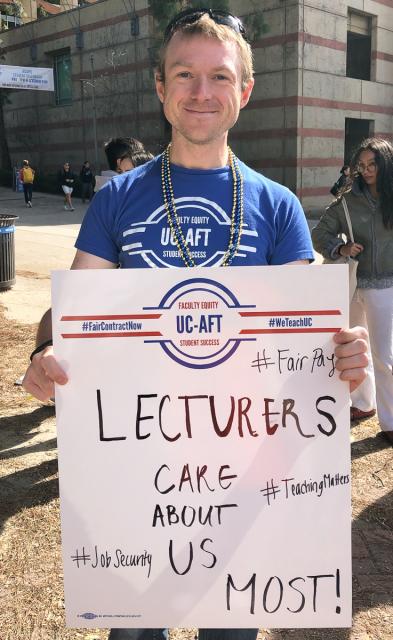

UC-AFT members demonstrated their solidarity on February 3 with mobilizations across the university system. The next negotiations are scheduled for March and April.

“Every chapter showed marked growth in union activity,” Brahinsky said. “We’re advancing the struggle and having a good time.”

The UCLA rally buoyed Wilson’s spirits. “Our movement is growing. Lecturers are very aware of and ready to stand up for our contract demands, and students and senate faculty are supporting us.”

She described picketers marching with a Dixieland jazz band through the UCLA campus to the administration building, where they delivered about 700 postcards — most signed by their students — supporting the lecturers’ demands.

“The postcards point to how important a role we play in their education,” she said, “especially when we mentor first-generation college students.”

The UC-AFT bargaining team has focused on job insecurity — often referred to as precarity — before tackling salary issues.

The goal, says UC-AFT President Mia McIver, is to ensure “that faculty who are great teachers — as demonstrated through a clear, fair and consistent review and reappointment process — can keep teaching the UC students who rely on them.”

Every California community college and Cal State campus already accords part-time faculty and lecturers that right, McIver adds.

But with a median salary of less than $20,000 annually and no compensation for much service and professional development work, money is a major issue. A series of previous contracts and the rising cost of living in California cities have raised the bar.

“The administration’s current offer is much lower,” McIver explains, “than recent raises won by academic researchers and research support staff, grad students, nurses, clerical-technical workers — and our very talented UC-AFT librarians.”

About 300 teaching assistants at UC Santa Cruz have launched an ongoing wildcat strike for a cost of living adjustment. Brahisnky said dozens of lecturers are walking picket lines with graduate students, undergrads, and faculty supporters. More than half of UC-AFT teaching faculty earn less than graduate students.

“The TAs and lecturers share precarity,” he said. “UC doesn’t value having employees with secure jobs, who earn a living salary and live in houses where you know your neighbors.”

The graduate student job action followed a January strike by about 50 skilled workers at UC Santa Cruz represented by AFSCME Local 3299. Joe Baxter, an electrician and union executive board member, described conditions in a guest commentary in the daily Santa Cruz Sentinel. AFSCME Local 3299 members recently ratified a new contract.

Baxter said the workers hadn’t had a raise in nearly three years. “We live in mobile homes, low-income housing, or rent hours away from our work because we are paid as much as 30 percent less than comparable workers at neighboring universities and local governments.”

Baxter also provided some stunning economic data about the University of California. “The student population is up 27 percent since 2008. University revenues have grown at nearly twice the rate of expenses over the same period. And spending on top administrators has gone up 65 percent over the past five years.”

The numbers don’t surprise Dolly Wilson, who said she has complained to UCLA administrators about the nursing school’s outdated medical lab. “We can’t see where those funds are going in teaching, so we have to assume they are being eaten up by administrative costs.”

Wilson has worked under three one-year contracts, and knows one lecturer in an advanced practice program with a contract for only one quarter. More than half the nursing school’s lecturers have left during the past five years, she said. “Everyone cites the workload.”

UC-AFT President McIver agrees. “We’re calling on the UC, as the nation’s foremost public university system, to live up to its mission statement,” she concluded, “and set the nationwide standard for contingent faculty working conditions.”

— By Steve Weingarten, CFT Reporter